Typography, Automation, and the Division of Labor: A Brief History

(original pages indicated in grey)

2

Typography was born in the mass-production mechanism of the printing press. It has thus always been implicated in automation — and, thereby, in the distinctly modern dynamics of overwork, underemployment, and runaway production. Transformations of labor and technology, however, have received scant attention in graphic design historiography. Philip Meggs’ landmark textbook A History of Graphic Design, for example, offers only the briefest hints of the social dislocations that accompanied automation in the printing trades. One reads, for example, that the first steam press in England was operated in a secret location to guard against sabotage, or that vaguely-defined “strikes and violence” greeted the first installations of typesetting machines.1 Otherwise, such histories tend to treat innovations in print technology as a politically neutral process of technical refinement. But the new machines and methods did not just drop from the heavens: their development was often materially supported by employers who aimed to speed up production, capture control over the work process, and even break strikes.

3

Modernity, Modernism, and the Graphic Designer

As the design historian Adrian Forty has documented, industrial and graphic design emerged with the capitalist division of labor; both professions, in turn, catalyzed further divisions and fragmentations of work.2 In eighteenth-century crafts like ceramics and printed fabrics, the erosion of trade knowledge was accompanied by the rise of a new role in production: that of the “modeller.”3 Usually hired from outside of the trade, these early designers were more dependably in touch with bourgeois taste than craftspeople were. In Josiah Wedgwood’s ceramic works, stylistic concerns were conditioned by a need to simplify production into a rigid series of straightforward tasks, in which there was little occasion for variation between workers. The contemporaneous vogue for Neoclassicism, with its simplified geometry and restrained ornament, provided an ideal opportunity to streamline production — with the express goal, in Wedgwood’s words, of making “such Machines of the Men as cannot err.”4

As critical historians from Karl Marx to Harry Braverman and David Noble have shown, the progress of capitalism’s division of labor entails a gradual transfer of control and planning from the factory floor to management. But the resulting degradation and cheapening of work was noticed almost from the beginning: notably by Wedgwood’s contemporary Adam Smith. In the opening chapter to The Wealth of Nations, Smith explains the production process in a new type of pin factory.5 Here, the capitalist has not simply gathered formerly-independent artisans to practice their trade → 4 side-by-side — instead, he has exploded the pin-making process into a line along which each laborer only cuts, sharpens, or polishes. Smith notes the miraculous extension of productivity in a process thus rationalized; elsewhere, however, he worries that the “great body of the people” will increasingly fill their days repeating the same handful of tasks.

The man whose whole life is spent performing a few simple operations, of which the effects too are, perhaps, always the same … has no occasion to exert his understanding, or to exercise his invention…. He naturally loses, therefore, the habit of such exertion, and generally becomes as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become.6

This same image was on John Ruskin’s mind in 1853, as he formulated what would become a central text for the Arts & Crafts movement’s anti-industrial critique. In “The Nature of the Gothic,” Ruskin mourns “the little piece of intelligence” rationed out to the factory worker, which “exhausts itself in making the point of a pin.”7 For Ruskin, the division of labor is more accurately the division of the laborers themselves: these abundant pins, he writes, are polished with mere “crumbs” of human capacities.8 The essay was republished by William Morris’ Kelmscott Press in 1892. Arriving at the end of a career rich in the paradoxes of an anti-capitalist design practice, Kelmscott was Morris’ attempt to restore aesthetic unity to the book while keeping skilled craftspeople employed at higher-than-average wages. Though Morris believed that the form of the book had been betrayed by industrial shoddiness, the scale of his undertaking still necessitated some modernization of the traditional work process.9 Kelmscott books nonetheless remained so expensive to produce that Morris was trapped, as he lamented, “ministering to the swinish luxury of the rich.”10

In the early twentieth-century United States, Morris’ legacy would be refashioned in a context of accelerating industrial transformation. Frank Lloyd Wright came to believe that Morris’ desired reconciliation between art, labor, and leisure was likely to be delivered by mechanization itself.11 For Wright, the machine — centrally illustrated by the printing press — had to be grasped for what it had → 5 become: “intellect mastering the drudgery of the earth.”12 The “meaningless torture” inflicted on workers and materials alike could now be swept away, Wright argued, as long as designers could part with anachronistic practices of ornamentation.13 Meanwhile, American commercial artists were falling “under the Arts & Crafts spell” and emerging as freelance specialists in book typography.14 Bruce Rogers and Frederic Goudy, for example, took on Morris’ aesthetic standards while largely ignoring his concerns about the social contradictions of large-scale production. It was Goudy’s student W.A. Dwiggins who would later popularize the phrase “graphic design” to describe this emerging position in print’s division of labor.15 The workshops of these early graphic designers were characterized by a clarified managerial role for the designer, a more rationalized division of labor below and, finally, an embrace of labor-saving technology in typesetting and printing.16

Across the ocean, meanwhile, a more explicitly socialist embrace of industry had produced the modernist “machine aesthetic.” Echoing and radicalizing Wright, the Constructivist manifesto of 1922 declared war on traditional art and pledged a conditional allegiance to the machine: Constructivists would be both technology’s “first fighting and punitive force” and its “last slave-workers.”17 At the same time, the Bauhaus was moving away from its Arts & Crafts roots. The school had initially been organized along guild lines: composed not of students and professors, but of masters, journeymen, and apprentices.18 In transitioning to an emphasis on industrial production, Bauhaus designers synthesized compositional lessons from Futurism, Dada, and Constructivism. One uniting theme of these movements had been a desire to alter the experience of reading by exploding the strictures of the letterpress. In each case, photomechanical techniques promised a way out. In the Bauhaus graphics studios, László Moholy-Nagy continued in this vein, developing a montage practice he termed “Typophoto.”

In the USSR, El Lissitzky theorized the epistemological and technical aspects of this blurring of text and image. The text-image, he surmised, could be put to work perfecting the human sensorium: revolutionized book forms would yield a “perpetual sharpening of → 6 the optic nerve.”19 Lissitzky also read early attempts at phototypography in the context of a historical tendency toward lightness and mobility: “The amount of material used is decreasing, we are dematerializing, cumbersome masses of material are being supplanted by released energies.”20 Such a process would culminate, as he cryptically wrote in 1926, in a final transcendence of print itself: “the electro-library.”21 After the midpoint of the century, metal type would indeed be supplanted by photographic media, in systems that were increasingly directed by “electro-libraries” of “dematerialized” data. By the 1990s, the convergences and displacements predicted by Lissitzky had yielded the digital hybridization of writing, typesetting, and imaging. In the end, however, these transformations owed more to the bottom lines of print capitalists than to the efforts of the radical modernists.

Modernism in design began with a vision of socialist industrial transformation — but by mid-century, it had become welded to the public image of the great capitalist conglomerates. Corporate boosters of modernism like the paperboard magnate Walter Paepke, a benefactor of the postwar “New Bauhaus” in Chicago, prophesied a world in which design would meld with management.22 Paepke argued that design could improve market competition between large firms tied to uniform machinery and wage agreements; internally, it could even be put to work on such “problems” as worker morale.23 Though modernism’s trajectory from utopian potential to capitalist instrumentalization is familiar to design history, parallel themes in the history of the printing trades have received less attention. The initial promise of technological innovations — to end, in Wright’s words, the “meaningless torture” of repetitive and inefficient labor — soon gave way to the sobering realities of deskilling and displacement. The contours of twentieth-century print technologies would be shaped in large part by struggles over automation and employment. The “released energies” of print’s dematerialization increasingly took the form of outmoded workers.

7

Industrial Rationalization and the Printer

The growing coherence and confidence of the graphic design profession is accompanied historically by the gradual fragmentation and decline of the printing trades.24 The job description of “printing” originally encompassed a set of knowledges that extended far beyond the point of contact between ink and paper. Early printers were often also type-founders, publishers, and booksellers.25 Even as the craft became more specialized, printing still involved typesetting and composing pages, which often extended to a role in writing. According to union typesetter and historian Henry Rosemont, newspaper printers in the mid-nineteenth century relied on a broad but informal education in “language, history, geography and other subjects,” which enabled them to produce entire articles from telegrams consisting of little more than the relevant nouns, verbs, and modifiers.26

Print workers thus held a strategic position in the circulation of public discourse, which was simply not possible without them. They often took advantage of this position to educate themselves and to advocate for the interests of their trade. In addition to their obligatory literacy, they had access to the press as an organizing tool — an extreme rarity for manufacturing workers of the early industrial era. Journeyman printers became the first group of workers to go on → 8 strike in the United States, just a year after the Revolutionary War.27 As Régis Debray has documented, print workers would go on to play prominent roles in revolutionary movements around the world during the next two centuries.28

The printed book was, if not the first, then certainly the clearest early example of the world of standardized, mass-produced commodities to come. And as with any other commodity, print production required “labor-saving” innovations to keep competing firms profitable. More efficient inventions often rendered the work less taxing and dangerous, but the primary motivation for their adoption was always the reduction of labor costs — resulting in layoffs or slashed hours. Print workers often found themselves fighting technologies that promised to ease the burden of their labor. Rosemont offers the example of a more efficient ink roller, invented in 1814 and vigorously resisted by American printers. The existing standard was a more rudimentary instrument that required periodic soakings in animal urine to keep it from hardening.29 Printers worked in consistently squalid, poorly-ventilated shops that contributed to lower-than-average life expectancies — but such conditions were clearly preferable to unemployment.30

Though Johannes Gutenberg’s fifteenth-century press had scarcely changed in the intervening years, the first decades of the nineteenth century brought transformations far beyond the humble roller. Iron construction and steam power fundamentally changed not only the shape of the machine, but the entire work process that fed and maintained it. However, a major production bottleneck remained: the reproduction of writing still required the manual assembly of each word and line. Printing firms grew to be heavily reliant upon a workforce of typesetters who were both rigorously trained and militantly organized. During the 1880s, several attempts were made to mechanize the typesetting process. One particularly spectacular failure was the Paige Compositor, which bankrupted its primary investor Mark Twain.31 As Twain is said to have boasted shortly before the invention proved unfeasible, the Paige could “work like six men and do everything but drink, swear, and go out on strike.”32

Then in 1886 Ottmar Mergenthaler, a German engineer hired by an investors’ group that represented the major New York newspapers, presented the first working model of the Linotype machine. Like type composition by the old method, the Linotype utilized thin bits of metal; here, however, each bit carried the negative impression → 25

A series of plates occupy pages 9–24 of the pamphlet. Read more at Other Forms.

of a character. Operators typed the characters into a line; justification was then carried out by a spacing mechanism that sealed the channel into which the characters had been set. Molten metal was then injected into the channel to form a full line in positive relief. After cooling, each “line o’ type” was stacked into columns and locked into page layouts for the press. While the Linotype was an expensive and somewhat risky investment, it delivered on promises of labor-cost savings, and in time it contributed to a dramatic enlargement of the size and circulation of the periodical press.

The trade at first dismissed these developments. As one printer’s newspaper reassuringly put it in 1891, Linotypes were mere “toys” for print capitalists with no practical background in the trade.33 Over the next decade, however, the threat became palpable. As one unemployed typesetter wrote in 1900, his place at the typecase had been usurped by a “monster” that eerily replicated his movements without need for food or human dignity.34 While a steady demand for the manual composition of headlines, advertisements, and other display applications muffled the effect slightly, the new work process soon touched off an employment crisis. Younger compositors scrambled to learn machine composition, while thousands of older or more narrowly-trained workers fell through the cracks. However, the International Typographical Union (ITU), which represented manual typesetters, was able to establish jurisdiction over the machines in strategic industrial centers around the turn of the century. In order to stave off the effects of the transformation, the ITU pushed for shorter workdays and encouraged early retirements.

As the popular press grew during the teens and twenties, typesetting employment stabilized and even expanded. The ITU grew in tandem, and soon became one of the most powerful unions in the United States. However, this position was soon threatened by a number of mutually-reinforcing technical innovations. First, teletypesetting enabled Linotypes to be driven like player pianos; encoded tape was poised to replace human typists.35 Second, a slew of phototypesetting inventions sought to replace the cumbersome “hot metal” process with typefaces stored on film. Giving typography a photochemical basis, in turn, allowed a more seamless integration of text and image, while also making typesetting more readily compatible with letterpress printing’s longtime competitor, offset lithography.

Like the beginnings of mechanized typesetting itself, efforts at moving beyond hot metal were piloted by newspapers. Early experiments with “cold type” were explicitly undertaken to break → 26 a wave of ITU strikes following the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which stripped organized labor of many of the bargaining rights it had won over the preceding decades.36 During a citywide pressroom strike that lasted from November 1947 to September 1949, the Chicago Tribune put its existing clerical staff to work on a new model of justifying typewriter whose output could be “pasted up” as camera-ready paper layouts, as opposed to being “locked up” in countless pieces of backward-reading metal.37 The Tribune’s infamous “Dewey Defeats Truman” edition of November 3, 1948 was typeset by strikebreakers, in a work process that now moved faster than the official ballot counts.38 While the quality of typewriter paste-up left something to be desired, these experiments strongly hinted at the possibility of producing a newspaper without the union.

The ITU was able to keep these challenges at bay throughout the mid-twentieth century. New contracts forbade machines like the teletypesetter, even though this meant that print-ready stories from the wire services had to be retyped by an ITU member on the premises.39 It wasn’t until 1964 that the New York City local signed a contract allowing Linotypes to be run on “outside tape” — on the condition, however, that employers paid 100% of the profits deriving from the new machinery into an “automation fund.”40 While this price was prohibitively steep for many firms, it opened the door to similar agreements on phototypesetting and, eventually, on computer systems. During the 1970s, the ITU began to draw down in exchange for the job and pension security of existing members.41 In the meantime, the new machines had already crept into areas of the industry with low union representation. A paradoxical result was that capital-intensive metropolitan papers like the New York Times were among last to make the transition. The final night of Linotype composition at the Times — July 1, 1978 — is memorialized in the documentary Farewell Etaoin Shrdlu, directed by ITU proofreader David Loeb Weiss.42 Among the film’s interviewees is a compositor who reflects on his 26 years in the industry:

[T]hat’s six years apprenticeship, 20 years journeyman. And these are words that aren’t just tossed around. … All the knowledge I’ve acquired over these 26 years is all locked up in → 27 a little box now called a computer. And I think probably most jobs are gonna end up the same way.43

Once more, the newspaper industry led the way in automation, and again the ITU attempted to train people in the new processes or encourage early retirements. In the earlier transformation, the work lost to Linotype composition was compensated by a gradual but decisive expansion of print production. This time, however, the further rationalization of typesetting destroyed older forms of work while narrowing the number of jobs in the new lines. As Lissitzky had predicted, metal gave way to film and paper; the material footprint of typography was shrinking. But as long as each text needed to be retyped to be typeset, labor-time savings were minimal. The widespread adoption of teletypesetting technology, however, allowed the storage and transmission of coded texts and, eventually, their formatting directions as well. By the 1970s, computer systems were beginning to dissolve typesetting into word processing. A centuries-old gap separating writing and printing was beginning to close — and this gap had been the very ground on which the ITU stood. The union suffered a long decline and finally dissolved in 1986, just as the personal computer was completing typography’s process of dematerialization. It was, at that time, the longest continuously-running union in U.S. history.44

28

The End of Modernism and the Last Typesetters

In the 1970s, print production involved a complex hierarchy of work processes, the final product of which was never fully visible until it had been printed. Designers could only approximate typographical treatments; directions on spacing, size, and weight were then handed off to phototypesetting shops to interpret in detail. A separate group of prepress specialists followed designers’ directions on variables like color density and image placement, and then “stripped” together disparate negatives to create a print-ready master. But despite the many hands through which such work passed, much of the period’s modernist-influenced design left the impression that it was the product a singular, detached mind.

Though there was still a high degree of churn in new machines and processes, this division of labor held stable until the arrival of Apple’s Macintosh computer in 1984. The personal computer centralized capacities formerly bound up in massive metal-founding operations, delicate apparatuses of type on film, or astronomically expensive, room-filling computers — to say nothing of the highly specialized workers that attended these machines, or of the systems of education and apprenticeship that such a workforce presupposed. Tasks that were once contracted out with some combination of strict direction and trust were now fully under the control of the individual designer — from the smallest details of letterforms to the organization of entire books. The Macintosh would soon offer image-editing capacities with no existing analogue, which in turn put pressure on commercial photographers and illustrators. The century since the invention of the Linotype had been one of “creative destruction” in the print industry: novel forms of work appeared suddenly and disruptively, only to be rendered obsolete in their turn. Once the brake provided by ITU contracts was removed, this process could accelerate unabated.

29

By the mid-1980s, typographical technology had reached a height of modernized seamlessness which, ironically, contributed to the decline of modernism’s hegemony in graphic design. New design software facilitated effects like layering and distortion, which were quickly put to use in visual polemics against modernist clarity. Formal complexity and semantic confusion in graphic design had a long pre-Macintosh history — stretching at least as far back as the late-1960s letterpress experiments of Wolfgang Weingart. In the 1980s, however, graphic designers raised the stakes of these experiments by linking them to contemporaneous developments in the academy: in particular, to the “linguistic” and “cultural turns” in the humanities.45 Terms like “deconstruction” and “post-structuralism” were applied to the printed page in ways that often required little familiarity with the theories in question. The grid — increasingly understood as a symbol of authoritarian and, perhaps, Eurocentric rationality — was parodied, skewed, or thrown aside entirely. Designers arranged texts into ambiguous formations, and designed new typefaces that intentionally thwarted legibility.

By the 1990s, the postmodernist critique of modern rationality and power had grown more rigorous. However, the movement’s theorists showed little interest in grasping capitalism as a determining context for their theory and practice; transformations in the political economy of print were thus largely ignored. When, in 1997, Emigre published a rare acknowledgment that entire industries were collapsing next door, it was with a heavy dose of schadenfreude:

[M]any of the printers who have gone out of business over the last quarter century deserved their fate. The grassroots of the printing trade is, after all, notoriously conservative, protectionist, and sexist.46

While prepress and printing — like most American trades — tended toward a narrowly white male membership and self-image, the heaviest losses in the industry from the 1980s forward were in fact suffered by the largely non-unionized workforce of the cold type shops. Compared to the membership of the ITU, these workers were disproportionately women and people of color.47

The postmodernists’ focus on cultural intervention often neglected the material contingencies of the practice. Semiotic theory and cultural studies opened vistas to broad contexts of symbolic → 30 circulation, but often at the cost of such bare facts as design’s own relationship to waged work. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that a new generation of practitioners has taken a more archaeological approach to the labor of design. In the recent documentaries Linotype: The Film (2012) and Graphic Means: A History of Graphic Design Production (2016) — both directed by practicing graphic designers — histories of print production expose deeper issues of deskilling, unemployment, and deindustrialization.48 These documentaries elegantly organize a complex history of print technology, and the present essay would admittedly have been impossible without them. However, both ultimately elide the capitalist labor dynamics that would explain their own narratives.

Douglas Wilson’s Linotype stirringly evokes the lost world of hot metal through humanizing portraits of the workers who kept it running.49 For example, in a near-reprise of his role as the narrator of Farewell Etaoin Shrdlu, the late Carl Schlesinger makes frequent appearances. The filmmakers include footage of him singing and tap dancing, and they indulge him as he tells a long-winded story about the time he met Marilyn Monroe. A casual viewer would never know that Schlesinger was also a lifelong member of the ITU, or that he coauthored an important book on the union’s automation strategy.50 Despite its exhaustiveness, in fact, Linotype manages to bracket the union’s existence altogether. Briar Levit’s Graphic Means takes up where Linotype leaves off — impressively condensing the jumble of machines that bridged the hot type and digital eras.51 Graphic Means directly addresses the role of the ITU and, further, the gendered division that arose between unionized hot type shops and “open” cold type shops. However, the decline of the union is presented as a technical inevitability and even as a refutation of male privilege; the phototypesetting bosses interviewed seem to be speaking as feminists when they say that “the girls” did equally admirable work for half the wages.52 The vulnerability of non-unionized women to the next wave of automation, meanwhile, is never addressed.

While typesetting has disappeared as a distinct job, it would be too simple to say that it was automated out of existence. Rather, since the late twentieth century the job description of the graphic designer has expanded to include tasks once carried out by the earliest printers. Now that we have considered the standpoints of both modernist radicals and extinct print workers, the contemporary situation of → 31 the graphic designer should appear somewhat absurd. Capitalist technological development has rendered texts and images almost infinitely reproducible — and has built unfathomable electro-libraries in the process. But despite this gigantic aggregation of productive force, it is still necessary to put people to work moving words and pictures around, most often in the service of brand competition among otherwise identical commodities. What confronts us is not a world in which machines have freed people from work, but one of mass unemployment, in which some of the most celebrated “innovations” are apps that facilitate short-term, low-wage, benefit-less contracts.

If graphic designers became typesetters, they may turn out to be the last typesetters. The design software that repackaged the knowledge and skill of the printing trades seemed at first to deliver a dreamed-of autonomy to graphic design as a profession. But because these technologies were off-the-shelf consumer products, trained and credentialed designers have less and less of a monopoly on the medium. A general facility with image and text has bled into general literacy — due in no small part to the ease of pirating such “immaterial” commodities as Photoshop. In the contemporary design press, articles on apps like TaskRabbit and Fiverr, or a future role for AI in the automation of design decisions, recall the mix of anxiety and reassurance that characterized coverage of the Linotype nearly 130 years ago.53 These projected “disruptions” may well turn out to be empty hype. But whatever is in store for graphic design in the coming decades, it will be impossible to understand without accounting for the capitalist constraints and imperatives that have shaped the practice from the beginning.

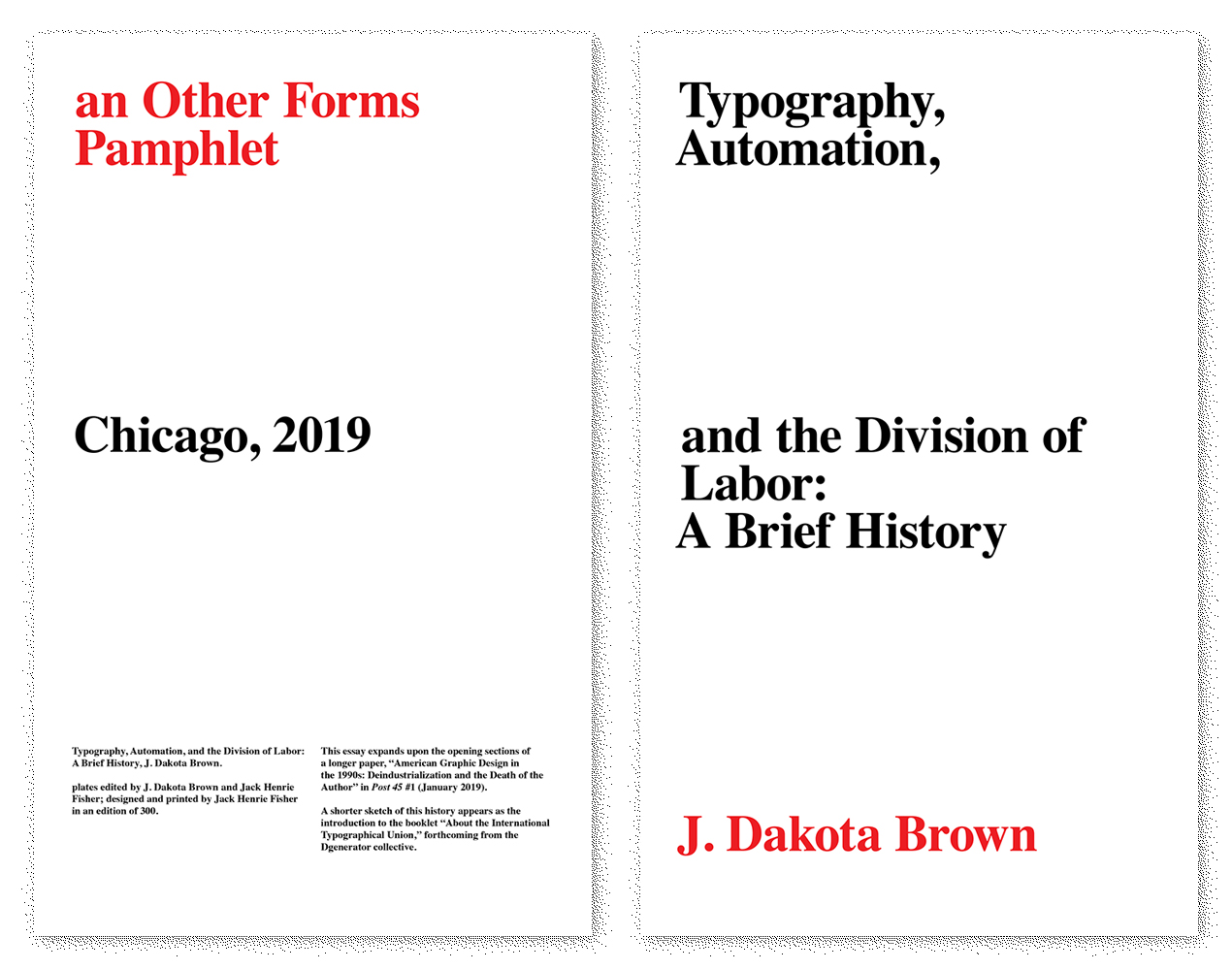

“Typography, Automation, and the Division of Labor: A Brief History” (2019) was published in an edition of 300 by Other Forms. The pamphlet was designed and printed by Jack Fisher, who also contributed valuable image research. Many thanks to Jack as well as Alan Smart for their feedback on early drafts.

-

Philip B. Meggs and Alston W. Purvis, Meggs’ History of Graphic Design. (New Jersey: Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2012), 151, 153.

-

Forty, Adrian. Objects of Desire: Design and Society since 1750. (London: Thames & Hudson, 2005).

-

Ibid., 24–26.

-

Ibid., 33.

-

Smith, Adam, and Edwin Cannan. The Wealth of Nations. (New York: Bantam Books, 2003), 10–11.

-

Ibid., 987.

-

Ruskin, John. “The Nature of Gothic” (1853). In The Industrial Design Reader, edited by Carma Gorman (New York: Allworth Press, 2003), 16.

-

Ibid.

-

Morris utilized photographic enlargers to study medieval type specimens; the ornate frames, illustrations, and initials of Kelmscott books were designed for modular interchangeability. Meggs and Purvis, Meggs’ History of Graphic Design, 181–185.

-

Kinross, Robin. Modern Typography: An Essay in Critical History. 2nd ed. (London: Hyphen Press, 2010), 45.

-

Wright, Frank Lloyd. “The Art and Craft of the Machine” (1901). In The Industrial Design Reader, edited by Carma Gorman. (New York: Allworth Press, 2003).

-

Ibid., 57.

-

Ibid., 59. Here Wright is making a point more famously and forcefully made nine years later by Adolf Loos, but one which does not depend on the facile Eurocentrism that one encounters in “Ornament and Crime.” See Loos, Adolf, and Adolf Opel. Ornament and Crime: Selected Essays. (Riverside: Ariadne Press, 1998).

-

Ibid., 60.

-

Meggs and Purvis, Meggs’ History of Graphic Design, 186. While Dwiggins is widely considered to have coined the term, Paul Shaw has unearthed earlier usages of “graphic design” in art school course catalogs of the early 1920s. Accessed August 10, 2019. https://www.paulshawletterdesign.com/2014/06/graphic-design-a-brief-terminological-history/

-

Kinross, Modern Typography: An Essay in Critical History, 60.

-

Rodchenko, Aleksandr, Varvara Stepanova, and Aleksei Gan. “Who We Are: Manifesto of the Constructivist Group” (1922). In Graphic Design Theory: Readings from the Field, edited by Helen Armstrong (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2009), 23.

-

Meggs and Purvis, Meggs’ History of Graphic Design, 315.

-

Lissitzky, El. “Our Book” (1926). In Graphic Design Theory: Readings From the Field, edited by Helen Armstrong (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2009), 30.

-

Ibid., 26. Lissitzky continues, “This process [collotype] involves a machine that transfers the composed type-matter onto a film, and a printing machine that copies the negative onto sensitive paper. Thus the enormous weight of type and the bucket of ink disappear….”

-

Merz No. 4, 1923.

-

Paepke also founded the International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA). For the first three years, the IDCA ran under the theme “Design as a Function of Management.” Wit, Wim De. “Claiming Room for Creativity: The Corporate Designer and IDCA.” In Design for the Corporate World 1950–1975, edited by Wim De Wit (London: Lund Humphries, 2017), 23.

-

Ibid., 24, 27.

-

This essay focuses on the emergence of typesetting as a distinct specialization within printing, and its later melding with graphic design practice. There is a longer story to tell, however, about the aesthetic deskilling of printers as they became service providers for graphic design and advertising. See David Jury, Graphic Design Before Graphic Designers: The Printer as Designer and Craftsman 1700–1914. (London: Thames & Hudson, 2012).

-

Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin, The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing, 1450–1800. (London: Verso, 2010), 128–166.

-

“For years after the telegraph was invented… [m]essages were sent to the newspapers in ‘skeleton form’; a good compositor… could set a thousand ems of type from 25 words of telegraphic copy.” Henry Rosemont, American Labor’s First Strike: Articles on Benjamin Franklin, the 1786 Philadelphia Journeymen’s Strike, Early Printers’ Unions in the U.S., and Their Legacy (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr, 2006), 86–87.

-

Ibid., 9–47.

-

Régis Debray. “Socialism: A Life-Cycle.” New Left Review 46 (2007).

-

Rosemont, American Labor’s First Strike, 57–58.

-

Ibid., 85.

-

“By 1887 Twain had invested a total of $50,000…. He bought the rights to the machine outright in 1889, and within a few more years, the machine, among a series of bad speculations, bankrupted him. The Paige had over 18,000 parts.” Frank Romano, History of the Phototypesetting Era (San Luis Obispo: Graphic Communication Institute, 2014), 32.

-

Harry Kelber and Carl Schlesinger, Union Printers and Controlled Automation (New York: Free Press, 1967), 3.

-

“The Typesetting Machine.” Typographical Journal, February 2, 1891, 4.

-

The anonymous typesetter’s poem says of the Linotype, “Look not upon it when it is in operation, for its conscience is seared with molten lead, and after you are gone it moves along just the same, and careth not at all whether you fill your stomach with angel’s food or corn cobs.” Anonymous, “The Linotype Has Come to Town.” Typographical Journal, August 15, 1900, 154.

-

Teletypesetting evolved from Morse code and the stock ticker; it would go on to form the basis for early computing memory.

-

A precedent had been set the previous year in Florida. An ITU strike at the St. Petersburg Times was defeated after publisher Nelson Poyntor invested in two new typewriter technologies (Varityper and Underwood Electric); he then “hired women to work on them.” Romano, History of the Phototypesetting Era, 25.

-

Ibid., 43.

-

Ibid.

-

“This practice — called ‘reproduction’ by the union, and ‘bogus’ by everyone else — may have been the most maddening expense publishers dealt with.” Ibid., 44.

-

Kelber and Schlesinger, Union Printers and Controlled Automation. 224–226.

-

For more on the last days of the ITU, see my interview with typesetter and union organizer Michael Neuschatz. “As the Ink Fades: An Interview with Michael Neuschatz.” Jacobin. Accessed October 15, 2018. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2017/09/typesetting-union-technology-automation-printing.

-

Farewell Etaoin Shrdlu: An Age-old Printing Process Gives Way to Modern Technology, directed by David Loeb Weiss (The New York Times Company, 1980), 29 min. “Etaoin Shrdlu” was a string of letters punched into the machine to indicate a typing error.

-

This segment reappears in the recent documentary Linotype, discussed below. The editors pointedly cut away before the last sentence on the likely future of automation.

-

At this time, remaining ITU locals were either absorbed into the Communications Workers of America or the Teamsters.

-

At the Cranbrook Academy of Art’s graduate design program, for example, digital experimentation and theory arrived almost simultaneously. Students were forming reading groups on postmodernism in the mid-1980s, just as the first computer lab was being set up — with hardware and software directly donated by Apple. Interview with Glen Suokko, Emigre 11 (1989): 8.

-

Marshall, Alan. “Decay and Renewal in Typeface Markets,” Emigre 42 (1997): 20.

-

For more on the ITU’s collision with race, gender, and technology in the 1970s and ‘80s, see “As the Ink Fades: An Interview with Michael Neuschatz.” Jacobin. op cit.

-

See also Typeface (2009), Sign Painters (2013), and Pressing On: The Letterpress Film (2016). It seems no accident that these films were all produced in the decade since the financial disasters of 2008; perhaps our period of intensifying “disruptions” in work and life draws attention to others like it.

-

Linotype: The Film, DVD. Dir. Douglas Wilson, 2012.

-

Kelber and Schlesinger, Union Printers and Controlled Automation. op. cit.

-

Graphic Means: A History of Graphic Design Production, DVD. Dir. Briar Levit, 2016.

-

While women held leadership positions in some ITU locals, and cold type shops were far from uniformly staffed by women, the divide was pronounced enough that cold type shop workers were colloquially referred to as “girls.” Romano, History of the Phototypesetting Era, 41.

-

Sacha Greif, “What kind of logo do you get for $5?” Aiga.org. Accessed August 10, 2019. https://dev.aiga.org/why-you-should-pay-morethan-5-dollars-for-logos. See also Jason Selentis, “When Websites Design Themselves,” Wired. Accessed August 10, 2019. https://www.wired.com/story/when-websites-design-themselves/